ORC’s Head of Research Julia Cooper reflects on her recent trip to Germany to attend a workshop focused on reducing pesticides in agriculture.

Last month I had the pleasure of attending a workshop on “Experiences, future developments and needs for sustainable crop protection” hosted by a team from the Institute for Agro-ecology and Biodiversity (IFAB), the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), and Lund University, Sweden. Together this consortium is exploring strategies to reduce environmental risks posed by pesticides, particularly policies that support farmers to minimise pesticide dependence and support biodiversity in agricultural landscapes. The project is funded by the German Environment Agency who are on a serious mission to reduce pesticide use in German farming systems.

This was a great opportunity to shout about the work we have been doing at ORC linked to reductions in pesticide use, particularly the Oper8 project. I highlighted Oper8’s work in partnership with the LiveSeeding project on competitive cultivars, showing some of the results from our farmer participatory trials with Organic Arable that have identified some modern cultivars with potential for weed suppression. I also introduced the group to living mulches, pointing out that these are relevant to organic farmers seeking to suppress weeds without pesticides, as well as for conventional no-till farmers who are trying to reduce reliance on glyphosate.

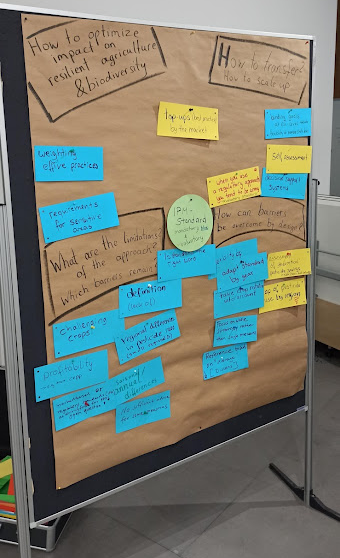

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) was a key theme of the event and the discussion around this approach (see Defra’s recent blog on new advice and guidance for farmers wanting to take up the SFI IPM options) reminded me of similar discussions about defining and codifying regenerative agriculture in the UK. IPM is not well defined, so how do we reward farmers who are using it when we can’t actually define it? Even Defra acknowledges that IPM is “not a fixed set of practices but a flexible approach to help you make the best decisions for your farm”. In the breakout discussions, organic certification schemes were often referred to with traces of envy as robust, clearly defined and enforceable standards that have no equivalent in the IPM or regenerative world. Nonetheless, promoting wholesale conversion to organic as a strategy to reduce pesticide use wasn’t recognised as a viable option for most of the people in attendance.

What did capture many people’s imaginations was the success of the IP-Suisse brand, presented by farmer and member, Mirjam Lüthi. IP-Suisse is a label linked to a set of standards that requires farmers to reduce pesticide use and implement IPM, use crop rotations, promote soil health and agroecosystem biodiversity, and maintain high animal welfare standards. Producers undergo inspections and are certified just like in organic systems. The label has a high degree of recognition by Swiss consumers and products sell for a slight premium in the marketplace. Based on Mirjam’s presentation, it seems that the only non-organic cropping practices used by IP-Suisse farmers are using herbicides for weed control and applying some synthetic fertiliser inputs. There may be some parallels with the LEAF Marque certification system here in the UK, but I got the impression that IP-Suisse was a more restrictive and comprehensive set of standards and it is verified by an independent third party (ProCert).

Examples like this always leave me conflicted. On the one hand, any programme that effectively supports farmers to reduce their reliance on pesticides must be a good thing. And perhaps some of these farmers will continue to transition away from herbicides and fertilisers and eventually convert to organic practices. We hear these arguments in favour of the regen ag movement in the UK. It is definitely raising awareness about the benefits of building soil health and demonstrating to many conventional farmers that there are ways to farm with fewer inputs of pesticides and fertilisers. But if the market for products grown in a more environmentally friendly way is finite, do products branded as more environmentally friendly take away market share from organics? This is a threat that makes many of us in the sector uneasy.

Ultimately, rather than wringing our hands about the constantly evolving landscape of production system labels, we need to stick to our messaging that organic farming is the gold standard for environmentally friendly farming. As well as promoting this message, we need to focus our research on the barriers to its uptake, particularly the challenges with weed pressure, nutrient supply and arable crop yields. This will benefit all farmers seeking to farm in a more environmentally friendly way, and just might result in some of them finding they have inadvertently transitioned to organic farming!